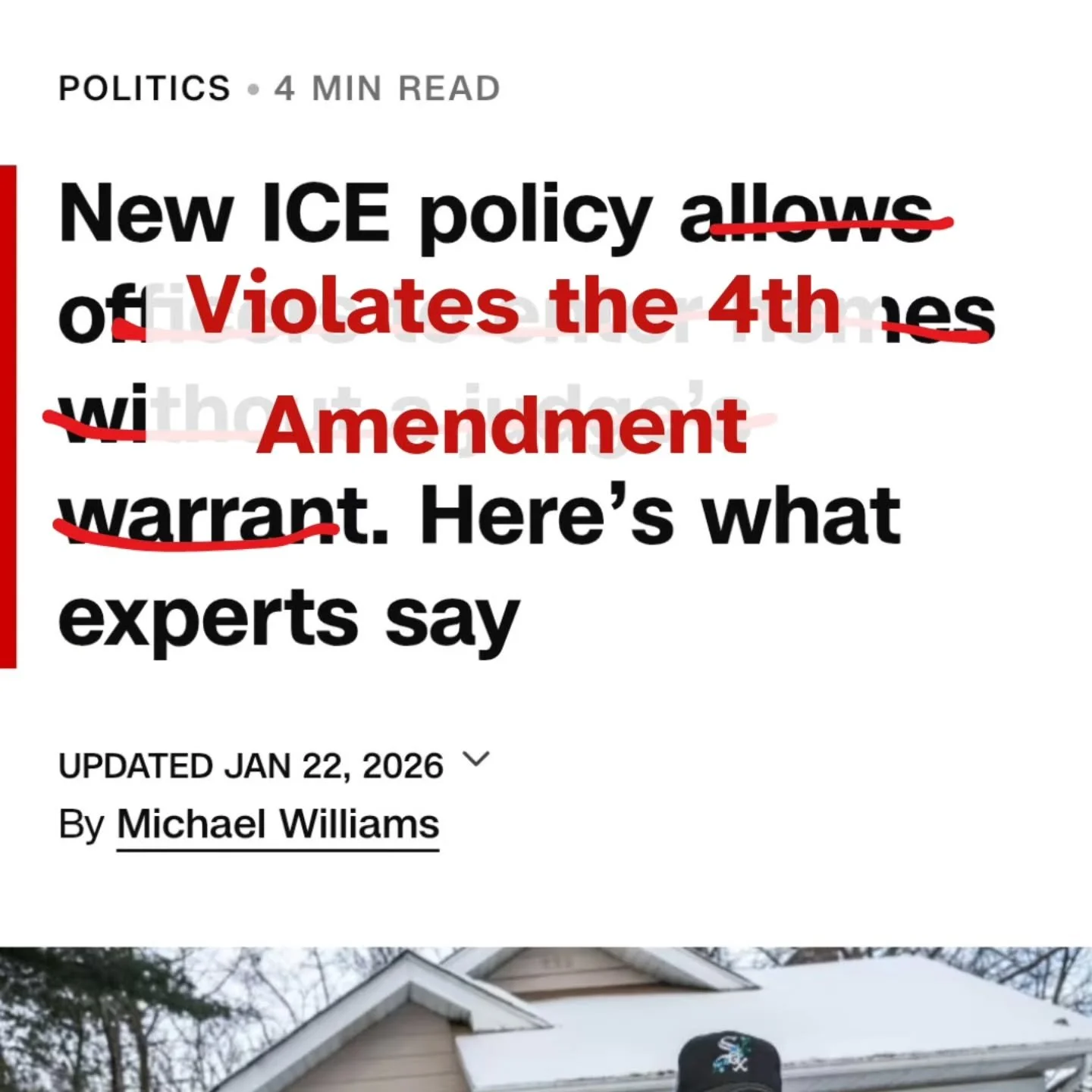

Breaking News

*

Breaking News *

While I update my blog when I have big news, you will find more up-to-date information on my socials. Click here to follow my accounts on the your preferred social site.

While I update my blog when I have big news, you will find more up-to-date information on my socials. Click here to follow my accounts on the your preferred social site.